UNDER THE BEDS.

Well I wasn’t around when Melbourne’s Coldicutt and Mathews were crossing swords with ASIO in the forties but I was there for the Great Red Scares of the 1950s.

Up to that point, the film people had all got along quite nicely in a we-all-did-in-Hitler-together atmosphere. The church groups ran BATTLESHIP POTEMKIN and the

leftists put on MONSIEUR VINCENT - on the principle that they were works of

art. They’d go to one another’s Xmas parties.

The problem was that everyone showed the same forty odd films. I kept on seeing John

Huston’s WE WERE STRANGERS, BERLIN OLYMPICS, SPANISH EARTH or BACK OF BEYOND. The D.of I.’s THE QUEEN IN AUSTRALIA got a run because it was so much nicer than the (American owned) Movietone version. The British Film Institute publications and Penguin Film Review were Holy Writ, even though a lot of their revered material - include nearly all Luchino Visconti or Luis Buñuel - hadn’t been aired here. Discussions centered on whether Eisenstein or Pudovkin was the true artist.

The problem was that everyone showed the same forty odd films. I kept on seeing John

Huston’s WE WERE STRANGERS, BERLIN OLYMPICS, SPANISH EARTH or BACK OF BEYOND. The D.of I.’s THE QUEEN IN AUSTRALIA got a run because it was so much nicer than the (American owned) Movietone version. The British Film Institute publications and Penguin Film Review were Holy Writ, even though a lot of their revered material - include nearly all Luchino Visconti or Luis Buñuel - hadn’t been aired here. Discussions centered on whether Eisenstein or Pudovkin was the true artist.

This was a bad fit with my own experience of cinema, derived from Newtown

Majestic, The Capitol and judicious use of the kiddie matinees which had

provided me with NANOOK OF THE NORTH, De Mille’s CRUSADES, the Fleischer

Brothers and METROPOLIS. To these the Savoy

added Jean Cocteau and Martine Carole. The Americans, with their veneration of David Wark Griffith and 1939 Hollywood seemed a better proposition.

I was as curious as the next man about the leftist material - the Russian

SADKO, the American NATIVE LAND

and SALT OF THE EARTH, the Chinese BUTTERFLY LOVERS on their new colour stock that was near impossible to splice. To this

day I follow the career of Czechoslovakia’s

Otaka Vavra with some fascination. However my interest quickened when John

Howard Reid retaliated, showing a near complete Elia Kazan retrospective.

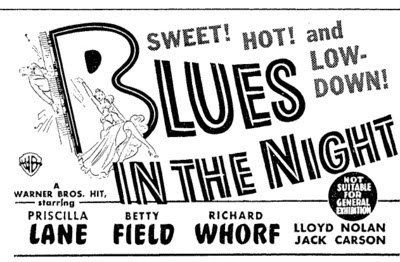

The big score seemed to be the old Hollywood

movies on which the often battered Sixteen Millimetre prints looked like they

would be our last glimpse of many notable titles - Litvak’s BLUES IN THE NIGHT,

George Stevens’ MORE THE MERRIER, Boleslawski’s THEODORA GOES WILD. Bad guess

actually. Though these never made it back onto projection screens, the new

commercial TV companies bought three digit studio packages, which turned

Australia into the best place in the world to see the early Hollywood sound

film for a decade, even if Nancy Carroll and John Gilbert were still

ignored by the old Sight & Sound readers, soon joined by the newly minted

Sam Fuller fans.

Then as now, there were

unfamiliar movies tucked away in under-used libraries. One had a hundred or so

US silents, many printed on the original tinted stock from the camera negatives

– Sidney Franklin’s THE SAFETY CURTAIN, William S. Hart in RETURN OF DRAW

EGAN and the William Seiter - Lewis Milestone LISTEN LESTER. Along with, these

you could find Gallone’s ULTRIMI GIORNI DI POMPEII or the short films of

William Cameron-Menzies, Danielle Darrieux in RETOUR À L’AUBE and a raft of intriguing British material - Conrad Veidt in UNDER THE RED ROBE, the

Powell-Pressberger SMALL BACK ROOM, Doug Fairbanks in ACCUSED, Cary Grant in

THE AMAZING QUEST or George Arliss in DR. SYN.

|

All this changed brutally. As well as the ASIO spook activity, there was a fear

of the Communist world in the local high art circles. Many professionals were

alarmed at the humiliation of creative people like Eisenstein and Shostakovich in Russia, where portraits painter teams, combining on group canvases of receptions, were considered to be

the peak of Socialist Realism.

Whether Eisenstein was any less humiliated in Hollywood is speculative but concern over control

passing from artists to doctrinaire bureaucrats is legitimate. The

deterioration of the Czech film, after the ascent of the Communists, had been

remarkable and, closer to our time, Mainland ownership of Hong

Kong film has dropped it from being the world’s number two movie

industry to nowhere. It didn’t take long for a mixture of Political Correctness

and salaried bureaucracy to stifle the emerging seventies Australian film, either.

In the fifties Sydney, Neil Gunther’s Film User’s association set itself up to

steer things away from the ubiquitous Soviet block material and Andrea, a now forgotten tabloid

columnist, ran an item about finding a flier for the Sydney Film Society’s screening of a

(shock horror) Polish film about YOUNG CHOPIN, on her seat at the Sydney Film

Festival. “Non political, non sectarian I wonder", she fumed.

This was a trigger for much name calling and finger pointing. Selecting the

East German film DER RAT DER GÖTTER caused a split in the Sydney Film Society, with Robert

J. Connell’s dissident faction scurrying off to start their own screenings at

Anzac House.

I watched all this with some concern. I’d had good nights with Eddie Allison’s

Realists or the Kings Cross Film Club, as well as the Catholics - not to mention the

Christian Anti-Communist League, who had access to a killer library, including Project

20: NIGHTMARE IN RED and Stuart Rosenberg’s QUESTION 7. I’d found them all amiable people.

The declining Sydney Film Society was a

particular concern. The oldest group in the country, it had Stanley Hawes, John Heyer, Bruce Beresford and radio writer Colin Free on its

board at different times. The Society had imported INTOLERANCE and it was the one group to run regular, open previews of possible material.

I signed on, doing donkey work. To the standards

(LAURA, JOURNAL D’UN CURÉ DE COMPAGNE, POTEMKIN with the then new Kruikov

score) we added in some of the neglected films and continued to space this with

politically sensitive material. The audience seemed as willing to be amused by

Stalin as the comic sidekick in LENIN V OKTABRE, as they were prepared to

ponder the clerical anguish in Harald Braun’s NACHTWACHE (Lutherans and

Catholics combine post WW2). I premiered the Lindsay Anderson MARCH TO ALDERMASTON

(good cause - dreary film) but never could get Clouzot’s MANON (founding Israel) or Mike Curtiz’ SANTA

FE TRAIL (nasty abolitionists) into the schedule.

The Sydney Film Society did manage to draw respectable numbers for unfamiliar

work, organised joint showings with other groups, created translations of items like

Helmut Kaütner’s FILM OHNE TITEL, did 35mm. screenings on MÄDCHEN IN UNIFORM and the Germi-Fellini CAMINO DELLA SPERANZA. They utilised collectors, with Don

Harkness’ copy of the Syd Chaplin CHARLEY’S AUNT a hit. I suspect it was the world’s first such group to run any Anthony Mann.

Screenings became more frequent and numbers went back up, though never reaching those of the pre-confrontation days and it outlasted the disintegration of the

breakaway group by many years.

These disputes were never really about politics. They were about personalities.

The Anzac House lot themselves ran DER RAT DER GÖTTER - couldn’t find enough German films without it. The Sydney University Film Group dug its heels in

against Film Users but refused to support the Sydney Film Society over the even more obvious

red baiting.

It all became so acrimonious that many of the people, whose efforts and good

will the film societies had coasted on, just went home to their TVs, never to return. It

meant an end to the days of a the movement as a lobby of any consequence, though it had

generated the Festivals, the AFI and a few of the country’s more influential

critics. The Sydney specialist film scene’s

debilitated condition caused the center to shift to Victoria,

where film society types were more interested in the profits of the Melbourne

Film Festival. They even still sustain a Clayton’s Cinémathèque there.

Ten years after, at the height of the Vietnam war, Keith Gow joked about the

effect his work with warfies' film unit would have on his Film Australia security clearance

and their unit covering L.B.J.’s motorcade said they filmed one of the staff throwing

themselves in front of the Presidential limo. No one cared. That was the scariest part of

all.

EPILOGUE: David Stratton’s Sydney Film Festival inherited a movie called SONS

& DAUGHTERS, about the youth movement ‘Nam

protest in San Francisco.

Remembering the Andrea incident, the recently bearded director shifted from foot to foot.

Everyone over twenty five stormed out in the first ten minutes and the

sympathiser audience remaining cheered when Jane Fonda came on, cheered when

Joan Baez came on, cheered when the Hells Angels came on - and suddenly went

quiet, realising that the Angels were against the protesters and for the war.

(“This is America!”)

The rest of the film played in silence.

It’s not easy being trendy.

Barrie Pattison – this article first appeared in

Australian Film Files.

No comments:

Post a Comment