THE RETURN OF WILLIAM S. HART.

I’ve been on William Surrey Hart’s case for pretty much all my adult life. After a disappointing introduction with a clip jammed into the old RKO compilation, I snapped to attention at a screening of Kodak’s battered The Return of Draw Egan and was wowed by Hell’s Hinges which my Mark Donskoi fan fellow Sydney Film Society members assured me was a film to be laughed at not laughed with.

Down the years, odd pieces of Hart’s work came my way from collectors (Alan Saunders was strong on these) and European Cinémathèques. I have copies of some sitting on the shelf, including ones that Pordenone were showing this year.

Down the years, odd pieces of Hart’s work came my way from collectors (Alan Saunders was strong on these) and European Cinémathèques. I have copies of some sitting on the shelf, including ones that Pordenone were showing this year.

After such an extensive familiarisation I was ambivalent about the festival making his retrospective their center piece. The old buzz proved hard to recover faced with sixteen films drawn from his 1914 to 1918 Triangle Company collaboration with Thomas Ince and into his Paramount work, which we are assured was his best period, a notion that sits uneasily with Hart’s imposing final Wild Bill Hickock and Tumbleweeds.

The program included some of Hart’s two reelers: In the Sage Brush County (1914 - hold up man protects mine owner’s daughter carrying pay roll) The Man from Nowhere (1915 - treacherous saloon keeper hides water in the desert cf. The Law & Jake Wade) The Sheriff’s Streak of Yellow (1915 - law man spares outlaw son of his benefactor but redeems his reputation in their final face-off) The Taking of Luke McVane (1915 - law man and quarry fight off Indians) Bad Buck of Santa Ynez (1915 - fugitive halts his flight to bury a pioneer) A Knight of the Trails (1915 - reformed Mystery Bandit saves waitress from fortune hunter Frank Borzage) and Keno Bates Liar (1915 - gambler shields his cheating victim’s mum from the truth).

Hart’s feature-length movies are more mature and ambitious than the 20 short dramas he was batting out for Tom Ince in 1915, averaging two every month. Those were OK for their day but it’s the mature features which provide his claim to distinction, though the early films already offer bits of business identifying the Hart character - striking the match on his thumb, pausing on the sky line to circle his hat in the air - and the rest.

However the event that turned round my attitude to William S. Hart was Pordenone’s screening of The Narrow Trail of 1917 which may well be the actor-star’s best work, displacing Hell's Hinges as my long time favorite. I once tried to program that with The Devil's Doorway.

Here we kick off with a familiar plot line. The Nevardas outlaws, headed up by Bill Hart / Ice Harding, trap the wild horses, with our hero roping their leader, who we will recognize as Fritz the Pinto, bringing him down and telling him they’ll be spending a lot of time together.

Trouble is that, after his riding Fritz in their banditry, the animal has become recognisable and the other bad hats want Bill to get rid of him. No, that’s not on for our hero. The bond between man & horse is plausible and a key element of the plot.

On a stage hold up, masked Bill is smitten with (Australian) Sylvia Breamer traveling with her supposed Easterner business man uncle, Admiral Milton Ross. Bill quits the gang and passes himself off in Saddle City as a rancher, squiring Breamer around the western scenery. Turns out that both of them are presenting false faces which is a stronger dynamic than we are used to and gives this one a lot of its extra charge.

She refuses to join Ross’ scheme to cheat Bill’s out of his bank roll and leaves. Hart decides that she is the one “clean ” thing in his life and follows to San Franciso where he encounters Bob Kortman and his pugilist chum on the waterfront with the tall ships. The pair plan to shanghai him and start getting him drunk in the Barbary Coast saloon where the boxer’s match photos line the back room. However who should be queen of the dancing girls but Sylvia. Our hero is shocked (“If you’re bad, ain’t nobody in the world good”) and rejects her, angrily punching it out with the pug and having to (plausibly) take down half the customers in a bar brawl. When he’s decked them, the other half cheer him on.

Here we kick off with a familiar plot line. The Nevardas outlaws, headed up by Bill Hart / Ice Harding, trap the wild horses, with our hero roping their leader, who we will recognize as Fritz the Pinto, bringing him down and telling him they’ll be spending a lot of time together.

Trouble is that, after his riding Fritz in their banditry, the animal has become recognisable and the other bad hats want Bill to get rid of him. No, that’s not on for our hero. The bond between man & horse is plausible and a key element of the plot.

On a stage hold up, masked Bill is smitten with (Australian) Sylvia Breamer traveling with her supposed Easterner business man uncle, Admiral Milton Ross. Bill quits the gang and passes himself off in Saddle City as a rancher, squiring Breamer around the western scenery. Turns out that both of them are presenting false faces which is a stronger dynamic than we are used to and gives this one a lot of its extra charge.

She refuses to join Ross’ scheme to cheat Bill’s out of his bank roll and leaves. Hart decides that she is the one “clean ” thing in his life and follows to San Franciso where he encounters Bob Kortman and his pugilist chum on the waterfront with the tall ships. The pair plan to shanghai him and start getting him drunk in the Barbary Coast saloon where the boxer’s match photos line the back room. However who should be queen of the dancing girls but Sylvia. Our hero is shocked (“If you’re bad, ain’t nobody in the world good”) and rejects her, angrily punching it out with the pug and having to (plausibly) take down half the customers in a bar brawl. When he’s decked them, the other half cheer him on.

It’s back West and who should he find but Sylvia having rejected her sinful ways and returned to “the mountains where things are clean - clean - the only noble thing in my life and I want to remember it.” Bill re-assesses the situation and fesses up on his own lawless past. “I reckon I ought to ask your pardon.” The pair plan to start a new life and the way to bank roll this is for Bill win the town’s thousand dollar horse race. However down at the stable the cowboys opine that the Pinto looks like the fast animal the bandit used to ride and if it wins the big race, the sheriff will have all the proof he needs.

More entertaining than any film of 1917 has a right to be.

While a large part of Hart’s work has been circulating one way or another, Pordenone did

surface a couple of unfamiliar titles. The Gunfighter of 1916 had existed in various single

reel 9.5 mm. editions and fifteen minutes of thirty five millimeter turned up in Switzerland. A team of restorers lovingly gummed these together to make a plausible version of the original.

Hart figures there’s only one way out. He leaves his side irons with Sylvia and gallops to victory, snatching the prize money and and scooping her up - like the end of Hidden Fortress - from the trackside to ride into the sunset before the law can grab him. The race coverage is notably superior to that in the John M. Stahl In Old Kentucky of some ten years later.

More entertaining than any film of 1917 has a right to be.

While a large part of Hart’s work has been circulating one way or another, Pordenone did

surface a couple of unfamiliar titles. The Gunfighter of 1916 had existed in various single

reel 9.5 mm. editions and fifteen minutes of thirty five millimeter turned up in Switzerland. A team of restorers lovingly gummed these together to make a plausible version of the original.

|

| Hart & friends :The Gunfighter. |

In this one Hart is Cliff “The Killer” Hudspeth, leader of a gang of Arizona outlaws rival to Roy “El Salvador” Laidlaw’s band. Laidlaw’s side kick Milton Ross again is living it up in the Golden Fleece saloon, running of at the mouth on the things he would do if he ever confronted The Killer. Hart overhears him and throws him out of the bar humiliating the man. He knows that when he goes out into the street there will be a confrontation.

Stepping through the door he finds milliner the winning Margery Wilson there and warns her to take shelter. He kills Ross in a main street shoot out and Wilson is appalled at what she sees as an act of murderous brutality, confronting Hart. Shaken by her attack he makes off with the girl to his mountain hideaway where she comes to understand the fact that he is haunted by the memory of his victims and thoughts of his late mother. The pair bond and, to become worthy of her, The Killer swears he will never take another life. This relationship could only exist in a William S. Hart movie.

However a delegate from the State House arrives and offers our hero a pardon if he will eliminate the lawless El Salvador. This puts Hart in a spot, bound by his oath. However Laidlaw makes off with Wilson and to rescue her, Hart has to kill him, hoping that she will understand that he did it to protect her.

|

| Hart & Wilson : The Gunfighter. |

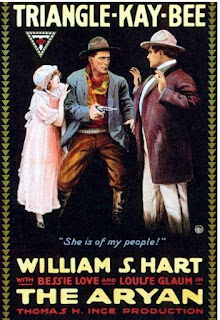

Prospector Hart arrives in Yellow Ridge with his hard earned poke of gold and the saloon crowd put dance hall floozie “The Firefly” - vamp Louise Glaum - in his path, keeping the telegram announcing his mother’s fatal illness away from Hart. The next day he wakes without the gold and finds the telegram. In a fury he blazes away at his deceivers and flings Glaum over his saddle, carrying her away to be his slatten-slave in an outlaw community where he has authority.

A wagon train of Mississippi farmers crossing the desert faces exhaustion and death. Hart is unmoved by their plight. However then eighteen year old Bessie Love at her most unsullied pleads with him and he’s faced with the decisive argument “She is of my people!” His hard heart softens.

Hart is not all that sensitive in his dealings with race. His films abound with murderous Mexicans occasionally played by Hawaiian Japanese, and we don’t get many noble red men either. The Indians are generally there to form “a circle of death” in the desert shoot out. Trying for something more shaded in Tumbleweeds has Bill using sign language, prompting Iron Eyes Cody, who was once hired in to sign for a single shot in The Dude Goes West, to comment “He signs like a squaw.” The strong, silent men could be remarkably snide, with Hart asserting Tom Mix dressed like a clown.

The Aryan is always mentioned as a key work from Hart but the pleasure of finally seeing this one is muted by it coming from the Argentine source that produced the extended Metropolis. The quality is equally dire, having gone through the same multiple inferior dupings.

In The Silent Man prospector Budd Marr / Hart comes off the desert with Nicodemus his donkey and a poke full of gold dust. What he wants in the Hello Thar saloon in Bakeoven town is long glasses of water, avoiding the fixed gaming wheel on his way to register his claim. Robert McKim’s villainous saloon owner, "Handsome Jack" Pressley, however has his floozy wife Dorcas Matthews vamp Bill into a crooked card game. A fight breaks out and our hero is jailed while the nasties steal his claim but, with a bandana over his face, Bill holds up the coach from Alkali on which McKim is transporting the gold and bringing back his new bride Viola Vale. Silent W.S. forces the dastard down the bank and makes off with the girl, taking her to Preachin’ Bill Hardy / George (White Gold) Nichols’s half built log church in the woods - which we just know is going to go up in smoke like the one in Hells Hinges.

The bearded cleric puts her straight about McKim’s existing marriage (complete with star burst silent swear words) and Viola and Bill go wander through the greenery before a surprise ending with a lynch mob and State Troopers.

Also on show was that old favorite 1916’s The Return of Draw Egan. One of the most widely circulated of Hart’s films, this opens with a quite presentable chase with a posse after the outlaw riders which ends with the bad men seemingly trapped in a hillside shack but leader Draw Egan / Hart has them use the floor trapdoor to escape, him going last with a wordless look back at the fallen comrade like Jimmy Stewart’s departing pause to consider the carnage from the battle with the Indians in The Naked Spur.

|

| Wilson & Hart :The Return of Draw Egan. |

Hart/Egan fetches up in the lawless Broken Hope Saloon where his ability to dispatch a bad hat impresses Yellow Dog Reform League official Mat Buckton. Just a glance at Buckton’s daughter, Margery Wilson again, convinces Bill to take the job of sheriff and he sorts out the roughneck element at speed. However old gang associate Arizona Joe / Robert McKim shows up and threatens to reveal Bill’s past, planning to loot the town from a base at the saloon where Louis Glaum is queen. Compare Noah Beery in 1930’s The Mighty or James Gregory in The Big Caper, films where the heavy’s mission is a Hells Hinges style destruction of the community. Bill can take no more and faces off against McKim on main street, knowing that the townspeople and Wilson will discover his sinful past. He disposes of the nasty but the grateful locals want him to hang on as law man.

Not a little simple minded and showing some of the rough edges of its day, this one remains agreeable entertainment. It’s probably the most conventional of Hart’s films.

His Blue Blazes' Rawden is made in 1918, that is after Birth of a Nation and Intolerance turned round film making. It has only the shadow of this development visible in Hart’s style. It is one of his frozen North movies where he comes on in a ‘coon skin cap - not not your full Davy Crocket but still a departure from his cowboy head gear. His Rawden is the master of a Timber Cove logging gang " "Hell's Babies, virile, grim men of strong pleasures and strong vices." There’s a hope that they will be shown as despoilers of the forest "God's vast cathedral" but any proto ecology theme vanishes almost immediately.

Instead things settle into a conflict in designer G. Harold Percival’s elaborate two storey timber Far North Saloon, where Bill has to duke it out with bruiser barman Jack Hoxie who is beaten for the first time and becomes his adherent, and to face off with the owner, Robert McKim (again), who dies trying to cheat Bill in a card game for the ownership of the establishment. His Indian-French mistress Maude George goes to the winner. The Stroheim actress makes a departure from the pale flowers and low life vamps that populate the Hart films, lusting after Bill with no scruples. This move from formula is not a real success.

The crunch is that McKim’s mother Gertrude Claire is on the way to see her son, bringing his young brother Robert Gordon. Dying McKim was promised that the new saloon owner will protect them from the truth and, stirred, Bill signs the place over to the family as belonging to the dead man and threatens to rip out the tongue of anyone who breathes the truth, carrying Claire through the river to the new grave where he has had her son’s marker replaced with a more lauditory description. Mad with desire, Maude however tells the brother, causing a shoot-out in which Bill is injured. He leaves in the freezing storm in which he may die and rejects George’s pleas to accompany him.

The film is a re-make of the Hart two reeler 1915 Keno Bates, Liar / The Last Card also shown, where Louis Glaum was the jealous saloon girl - and before that of 1914’s Broncho Billy’s Fatal Joke.

Hart already had the cowboy skills - handling guns & horses - that William Boyd, Gene Autry and Roy Rogers, even John Wayne and Buck Jones, needed to learn and you can recognise that. He belonged to the era of Mark Twain, Peter B. Klyne and Jack London where the hard men found themselves protecting women and children but he also looked forward to the grim vendetta westerns of Borden Chase, Philip Yordan and Niven Busch. It’s particularly interesting to find elements that will become familiar in the later Hollywood western already present here, possibly for the first time. The crooked card game in 1917’s The Silent Man prefigures My Darling Clemantine complete with the cards signaled by the bar girl and the giveaway reflection - in the brass lamp. Hart’s films are more like the mature John Ford westerns than Ford’s own silents.

Of course Hart did not make these films alone. He settled into the structure established by pioneer producer-writer-director Thomas H. Ince, a major player at his Santa Inez cañon Inceville studios. There were disputes about the director credit of the Hart westerns, however in retrospect we can see Hart as the active ingredient. Ince’s own major effort Civilization is ponderous and clumsy and even his own westerns like the 1914 Last of the Line suffer in comparison. Under Ince, Hart did find himself working with the most prestigious Hollywood writer of the silent period, C. Gardner Sullivan, later to script the J. Warren Kerrigan Captain Blood, All Quiet on the Western Front and sound Gary Cooper - De Mille spectaculars and working with newly promoted cameraman Joseph H. August who would film major works for John Ford (Seas Beneath, The Informer, They Were Expendable) and RKO (Gunga Din, The Devil & Daniel Webster). Writer-director Lambert Hillyer began a career which would have him working with later cowboy-stars, heading up the admirable 1936 Karloff piece The Invisible Ray and earning a small place in the collective awareness as directing Batman’s first screen appearance, in the 1943 serial. Even now it’s possible to spot distinguished collaborators’ input. We see August’s slanting sunshine from Hells Hinges come back again in the Laughton Hunchback of Notre Dame twenty years later. Hart stepping from wide shot to screen filling close up all the while in sharp forcus, is something which would defeat many cameramen for decades.

Making Fritz a prominent character, as he is in The Narrow Trail and Pinto Ben, promotes what appears to be their genuine bond. Hart may have innvovated the notion of co-star mount - think Tom Mix’s Just Tony or Roy Rogers’ My Pal Trigger. No one seems to know the name of Broncho Billy Anderson’s horse. Hopalong Cassidy on the other hand never seemed to mention Topper by name though, when California Carson goes to handle him, he’s warned “Take care of your own horse.” Lawyer Ginger Rogers bails up cowboy star Jack Carson's employers by pointing out they violate the no prominent co-star rule in his contract by the billing given his horse in Richard Wharf's 1951The Groom Wore Spurs.

We can also see the contempt for alcohol found in the later Hollywood western. Coming off the desert ready to register his claim clear headed in The Silent Man, Hart confines himself to his long glasses of water in the bar anticipating Shane’s “Sodee Pop”. Post prohibition cowboys took their status as role models seriously. Rex Bell orders buttermilk in the 1933 Diamond Trail and decks the gangster who sasses him over it. In Wide Open Town, a Hoppalong Cassidy in which the hero is again motivated by his protection of a little girl, bad guy Victor Jory taunts Hoppy about his refusing “a real drink” but when Jory goes for his gun he’s blinded by the whiskey he’d poured that Hoppy throws in his face.

Long before Woody Allen, Hart was getting stick for pairing with women half his age. That was easier for the critics than familiarising themselves with his work. Wolf Lowry shows Hart’s awareness in a plot where he is set to marry Margery Wilson, who passes off the photo of her young love Carl Ullman as a cousin. When he finds the truth, Hart / Lowry, who considered settling the matter with hot lead, leaves the couple to celebrate the ceremony he planned for himself and settles into the hard life on the distant Alaskan frontier.

The actresses in the Hart movies had notably better careers than their male associates. Frank Borzage was an Ince regular and went on to become one of Hollywood’s leading directors and Bob Kortman did persist into the fifties - but they were exceptions. I have no clear idea of what all-purpose supporting actor Robert McKim looked like. He comes on in different character make up each film.

By Contrast Margery Wilson was heroine of the Hugenot episode of Intolerance and did substantial work continuing into the twenties and becoming a writer-producer-director herself. The Toll Gate’s Anna Q. Nilsson became a major star in her own right. Edith Markey was Tarzan Elmo Lincoln’s Jane. Louis Glaum was Ince’s resident vamp achieving popularity which rivaled Theda Bara in films like Fred Niblo’s 1920 Sex. French intellectuals like Louis Delluc, Jean Cocteau and Charles Dullin compared her playing against a virginal Bessie Love, soon to be Hollywood’s most lively representative of Flaming Youth, to something out of Greek Tragedy. In the world of William S. Hart there were two kinds of women. Dorcas Matthews’s fallen wife has a back story with a wedding dress she wore “When I was good”.

It is hard to get round the dissonance between Hart’s appearance and that of the westerner

hero characters established by the covers of Dime Novels or the paintings of his friend Charles Russell, something not uncommon in series cowboys. Jack Perrin, Bob Steele, Swinging Sammy Baugh - or Audie Murphy - don’t look the part. It was in character for both Hart and Murphy to make their war bonds promotion shorts - Murphy’s Medal of Honour and Hart’s All Star Production of Patriotic Episodes for the Second Liberty Loan where he hams it up with Fairbanks, Pickford and Theodore Roberts. That was in the Pordenone season along with the synch. introduction he did for the re-issue of Tumbleweeds.

Making Fritz a prominent character, as he is in The Narrow Trail and Pinto Ben, promotes what appears to be their genuine bond. Hart may have innvovated the notion of co-star mount - think Tom Mix’s Just Tony or Roy Rogers’ My Pal Trigger. No one seems to know the name of Broncho Billy Anderson’s horse. Hopalong Cassidy on the other hand never seemed to mention Topper by name though, when California Carson goes to handle him, he’s warned “Take care of your own horse.” Lawyer Ginger Rogers bails up cowboy star Jack Carson's employers by pointing out they violate the no prominent co-star rule in his contract by the billing given his horse in Richard Wharf's 1951The Groom Wore Spurs.

We can also see the contempt for alcohol found in the later Hollywood western. Coming off the desert ready to register his claim clear headed in The Silent Man, Hart confines himself to his long glasses of water in the bar anticipating Shane’s “Sodee Pop”. Post prohibition cowboys took their status as role models seriously. Rex Bell orders buttermilk in the 1933 Diamond Trail and decks the gangster who sasses him over it. In Wide Open Town, a Hoppalong Cassidy in which the hero is again motivated by his protection of a little girl, bad guy Victor Jory taunts Hoppy about his refusing “a real drink” but when Jory goes for his gun he’s blinded by the whiskey he’d poured that Hoppy throws in his face.

Long before Woody Allen, Hart was getting stick for pairing with women half his age. That was easier for the critics than familiarising themselves with his work. Wolf Lowry shows Hart’s awareness in a plot where he is set to marry Margery Wilson, who passes off the photo of her young love Carl Ullman as a cousin. When he finds the truth, Hart / Lowry, who considered settling the matter with hot lead, leaves the couple to celebrate the ceremony he planned for himself and settles into the hard life on the distant Alaskan frontier.

The actresses in the Hart movies had notably better careers than their male associates. Frank Borzage was an Ince regular and went on to become one of Hollywood’s leading directors and Bob Kortman did persist into the fifties - but they were exceptions. I have no clear idea of what all-purpose supporting actor Robert McKim looked like. He comes on in different character make up each film.

By Contrast Margery Wilson was heroine of the Hugenot episode of Intolerance and did substantial work continuing into the twenties and becoming a writer-producer-director herself. The Toll Gate’s Anna Q. Nilsson became a major star in her own right. Edith Markey was Tarzan Elmo Lincoln’s Jane. Louis Glaum was Ince’s resident vamp achieving popularity which rivaled Theda Bara in films like Fred Niblo’s 1920 Sex. French intellectuals like Louis Delluc, Jean Cocteau and Charles Dullin compared her playing against a virginal Bessie Love, soon to be Hollywood’s most lively representative of Flaming Youth, to something out of Greek Tragedy. In the world of William S. Hart there were two kinds of women. Dorcas Matthews’s fallen wife has a back story with a wedding dress she wore “When I was good”.

It is hard to get round the dissonance between Hart’s appearance and that of the westerner

hero characters established by the covers of Dime Novels or the paintings of his friend Charles Russell, something not uncommon in series cowboys. Jack Perrin, Bob Steele, Swinging Sammy Baugh - or Audie Murphy - don’t look the part. It was in character for both Hart and Murphy to make their war bonds promotion shorts - Murphy’s Medal of Honour and Hart’s All Star Production of Patriotic Episodes for the Second Liberty Loan where he hams it up with Fairbanks, Pickford and Theodore Roberts. That was in the Pordenone season along with the synch. introduction he did for the re-issue of Tumbleweeds.

Hart’s critics said that he himself was the out of place element in his realistic frontier depictions. However Hart seems to have figured that out too. Seeing a large slice of his output together we recognise the actor’s long face framed by a pair of revolvers, held as if they really did have the weight of six lead rounds in them coming up in film after film, an image repeated in posters and publicity photos. We know the actor, like Murphy, as a key element of his imposing western tableaux. When he struggled to vary the formula - contemporary workman in The Whistle or Aztec Indian in The Captive God the magic wasn’t there.

It’s agreeable to find that after this large scale re-assessment, William S. Hart holds his place with D.W. Griffith, Louis Feuillade and Victor Sjöstrom as one of the first major talents to realise the nature and scope of the movies and that there's still an excitement to be had out of his work.

It’s agreeable to find that after this large scale re-assessment, William S. Hart holds his place with D.W. Griffith, Louis Feuillade and Victor Sjöstrom as one of the first major talents to realise the nature and scope of the movies and that there's still an excitement to be had out of his work.

Barrie Patison 2022