|

| Chahine |

|

| Menna Shalabi & Mohamed Henedy. |

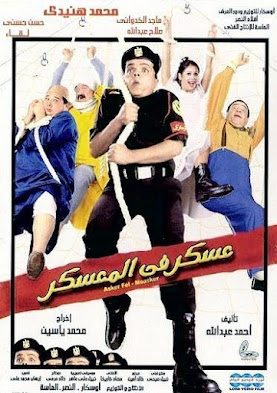

Muhammad Yasin’s 2003 Askar fi el-mu'askar/Asker Fel-Moasker/ Askar at the Camp/ Sodiers of the Camp, the earliest of the translated Henedi films, runs to some ambitious staging. It is done mainly in brief comic sketches, linked by scattered plot elements - military training, (cf. Bob Hope in Caught in the Draft among others) a blood feud (think Ugo Tognazzi in Questione d’onore), the friendship with chubby army buddy Maged El Kedwany (like Aamir Kahn in Laal Singh Chaddha), Moh’s wedding to the appealing Lekaa El Khomaisy or the disillusion of finding his history teacher uncle Salah Abdulla become Hassan Kolonia the Perfumer, a night club entertainer.

|

| Soldiers of the Camp. |

The wedding is the film’s high point with chanting women, a blazing torch parade, Moh on horseback with an AK 16, armed guards protecting the ceremony and checking guests while the couple huddle in a sandbag shelter. Complications involve Moh’s dad giving the bridal couple’s bedding to the bodyguards, along with the TV.

Our

hero’s army buddy Maged El Kedwany naturally turns out to be the son of

the enemy family. Despite all the security, El Kedwany is admitted as a

friend of the groom just by flashing an I.D. and comes under fire in

his own relatives’ raid, before he can do any avenging.

Moh

and the bride flee by train to Cairo, seeking once respectable uncle

Salah Abdulla. However he now shares a Cabaret stage with an energetic

redhead shimmy dancer, who is ambivalent about having the pair move

into her flat. She drags the bride into the bedroom and leaves the couch

to the men.

Uncle gets the newlyweds a job as costumed players in a Pharaonic show for tourists but the murderous feud catches up with them. Fleeing to a waste ground shanty, the lovers’ attempts to get it on are again thwarted. Sharing a truck load of sand has them once more frustrated, dumped on a building site.

For

a bit of cultural dissonance, how about Saadeya, the new wife, who Moh

had to threaten with a knife to get her to come across, now complaining

that she’s been a bride for three days and she’s still a virgin?

Moh’s attempt to

get a transfer away from the camp, where Metawali is also a soldier, is

rejected. Sharing the same bunkhouse proves fraught and Moh finds

himself on prisoner detail, hand cuffed to a soldier returning to his

home to be engulfed by his old neighbors before a suitably happy ending.

The

leads are winning and their material serves them well. Wide screen

colour production values are good and the unfamiliar setting catches

attention, rural local colour - Buffalo in the river, Moh saluting a

historic sculpture he passes - contrasted with metropolitan

landmarks - the Pointing Statue, the 6th of October Bridge or the fakey Cairo tourist show the pair are recruited into. This goes with

material like the scenes of military training - black uniforms in

choreographed hand to hand combat curiously like Beau Travaille.

Just when we are accepting the similarities with our own world we get

Moh protesting when his new wife goes marketing with her hair hanging

loose or the Sergeant’s first wife finding about the second.

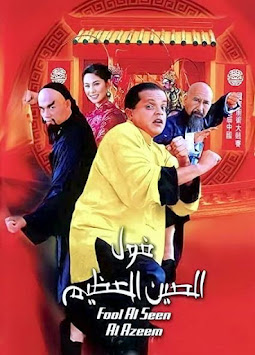

Also on show is Henedy’s most widely offered film, the 2004 Fool el seen el azeem /The Great Chinese Beans directed by Sherif Arafa.

Here

the young Moh, who just wants to use his 51% college pass to get an

education, is have trouble sleeping, when a burglar breaks in and demands

the whereabouts of his gang Czar grand father. At this point, his

murderous uncles appear, telling him he’s failed the courage test. They

are barely restrained from offing the kid, instead getting him up in a

padded muscles suit to conduct their drug buy, where he escapes leaving

them behind. So it’s a matter of packing him off to his singer mum who

he blinded (!) when he dropped the chandelier on her, during one of her

performances in a B&W flashback.

His

father in law has Moh substitute for him in an Iron Chef competition in

China (actually Thailand) sending him off with a note in Chinese that

says he is carrying drugs, stolen by his hapless fellow passenger while

our hero is sucked into the jetliner loo for five hours.

Moh

is collected by the fetching girl translator in a cab, whose driver

keeps on throwing away cell ‘phones with unwelcome messages. Our hero

finds a fellow Arab from Beirut in the finals but a Chinese gang,

knowing his mob background, figures Mohamed must be there as a hitman

and hires him to off the judge, which he avoids by slipping the

passenger’s laxative into the meals - ho ho.

|

| The Great Chines Beans |

At

the cooking contest in disguise, Moh emerges from behind the pillar in

his chef outfit and wins, scarpering from the assassins but helping a

family to victory by using his falling out of tree skill. These films

are not strong on logical development.

There’s

some obvious wire work, which they demonstrate under the end credits

and a few alien moments like the lead encouraging “pray to the prophet!”

and joining the Lebanese chef in Arabism.

The

locating stock shots are fuzzy digital transfers, like the Egypt Air

in-flight material but technical standards are quite good and the pacing

carries things, with the leads appealing.

The showpiece here is the new El Ens W El Nems / Humans vs. the Mongoose,

again directed Sharif Arafah and clearly a prestige product from its

home industry. This big screen, contemporary piece kicks off with

Henedi’s family trying to reassure the Parks Inspector that their Kids

Fun Fair haunted house exhibit is not scary, despite jump shock figures

dropping out of the ceiling as they tour.

We

shift to domestic comedy with the family sharing the crowded home

bathroom over Mohamed’s objections. Out on the street, he stops a bus

hitting not quite pretty Menna Shalabi - who proves a remarkable screen

presence. Turns out she’s a Djinn (think Three Thousand Years of Longing) who now can’t get enough of him, being

under pressure having aged past the point where she qualifies for an

arranged marriage. She invites Mohamed to visit her family home, reached

through a fog bank past submerged sculptures, under the guidance of

identical, towering, formal dress butlers.

| Humans and the Mongoose. |

He

recruits Mohamed for his confrontation with tailed genie Bayoumi Fouad,

who ends up back in the scummiest bottle on earth with the prospect of being

buried under a toilet for the next thousand years.

Shalabi

is anxious to get on with the fecundation (a light shines under the

bedroom door) but Moh, who’s been told her dad will eat him afterward,

is somehow reluctant. However she assures him she won’t let that happen

to the father of her offspring and her brother adds to his defense, with

the now liberated genie joining his team. “If death is inevitable, it

is a shame to die a coward.”

Moh’s long-lost father also shows up to guide him to the magician who produces the leather incantation and the bottled spell to be dropped into one of the lava pits (which one?) to stave off the Djinns.

Some

nice urban drone shots as punctuation, lots of CG, which is good enough

(battle with the Mongoose) in an area where spectacular is common. This

one constantly evokes Hollywood models, Jim Carey, Ghostbusters, Men in Black,

along with an abrupt Bollywood number, and is paced by inscrutable

references like Hano Bavela. The mix is one of the things that

hold attention along with backing the winning leads with talented

(unfamiliar to us) comics and superior production values.

From

the indications in this small sample, Henedi’s films become more

ambitious and more approachable as they go. Their scatology without

nudity is not for all tastes but kids will devour these.

|

| Ismail Yasine |

Henedi is a more gifted career comedian. I’d place him middle of a scale above Toto, Cantinflas and Jerry Lewis, on a par with Red Skelton before he expanded into TV and maybe shaded by Bob Hope, Lino Banfi, Fernandel and Adam Sandler.

Significantly these comedians are handled dismissively by critics and never make it into festivals. When the horror films were treated this way, their admirers started their own festivals and the work was accepted into the fold. This has never happened with the comics.

However there’s another buzz to be had out of watching Mohamed Henedi’s films. It’s like being faced with Mehboob Kahn and Nargis in the fifties or Sammo Hung and the Shaw Brothers in the seventies. Those films were a bridge into a whole world of film going which we vaguely knew existed but had never been invited to enter. There’s the lure that maybe we can repeat that experience. It could be misleading but Henedi projects an enormously sympathetic personality. His comic timing is impressive and he occupies a space at once familiar and surprising to us. It can’t be a bad idea to discover the way the Arab world thinks of popular entertainment. I enjoy that.